What Is Osteopathy?

Osteopathy is both a practice and a philosophy of healthcare. In practice, a Doctor of Osteopathy (DO) has traditionally used hands-on skills (Osteopathic Manipulative Treatment) to optimize the structural alignment of their patient’s body in order to improve the body’s capacity for motion and overall functioning. This approach is taken in accordance with the philosophy of Osteopathy, which affirms that the body is a single unit of function capable of self-healing because structure and function relate to each other at every level – from the level of the molecule, protein and cell, to the level of the tissue and organ, to the level of the whole individual. Sometimes the body just needs some assistance when it is stuck structurally to get back to its healthiest functioning.

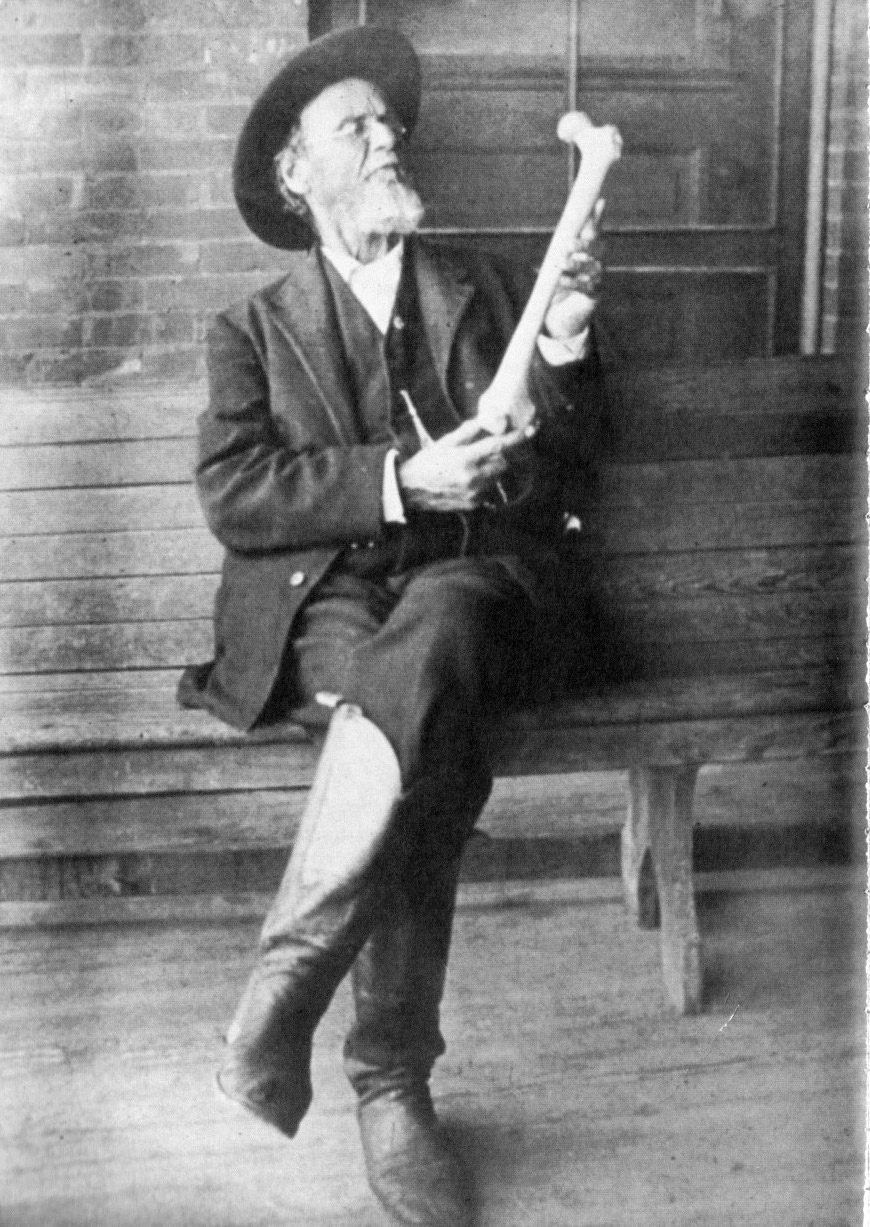

Osteopathy dates back to the 19th century frontier of the United States. It was originally elucidated by Andrew Taylor Still, MD, and has since spread throughout the world. Osteopaths attend specific medical schools where they recieve additional training in the manual diagnostic and treatment skills of osteopathy. Osteopaths, often alongside Allopathic Medical Doctors (MDs), undertake a residency after completing medical school, spending an additional three to seven (or more) years in supervised practice while specializing in any of the given medical disciplines like:

Family Practice

Internal Medicine

Surgery

Radiology

Osteopathic Manipulative Medicine

Cardiology

and many others.

DOs in the United States use a combination of allopathic (prescriptions, surgery, lab testing) and osteopathic (manual treatments intended to optimize the individual's structure and function) approaches in patient care, predominantly employing the hands-on skills of manipulative medicine without resorting to prescription drugs or surgery.

Finding Health

With his signature counsel to any aspiring Osteopath, "To find Health should be the object of the doctor. Anyone can find disease,"

Andrew Taylor Still, MD, DO, was advising those who would follow to train themselves to align with the inherent vitality present in each patient regardless of any coexisting pathology. He had come by this wisdom through his experience practicing as an American frontier physician in the late 19th century, an occupation that coupled well with his innate curiosity as an engineer. Furthermore, the deepening spirituality of a man who had faced intense personal loss (several of his children died after contracting meningitis) only to rebound to a life of service and intellectual refinement undoubtedly informed his ability to penetrate to and perceive the truth of the human condition. These factors combined had furnished him with a masterful knowledge of human anatomy and an understanding of human physiology that was ahead of his time. But more importantly they enabled him to recognize and commune with the underlying organizing principle of life: Health.

Still viewed Health as that always present, always perfect symbiosis between anatomy and physiology that supports life and adheres to certain general and recognizable patterns, but which is also uniquely and beautifully expressed in each individual. He came to realize through his own practice that encouraging his patients' unique expressions of Health (through manual interventions as well as through relational skillfulness and presence of mind) would serve to marshal the Health's ability to intelligently address from within what was most in need of change, and thereby to manifest a greater-still expression of Health. Still knew that this approach to treating patients, to support their own inherent abilities to express and more fully embody Health, far surpassed the then (and still) prevailing tendency to orient towards disease in an effort to destroy it by any means and with minimal regard for repercussions. Still’s way of orienting to Health addresses the needs of the whole of the individual by training the physician’s manual faculties, interpersonal abilities, and more than just the standard five senses to work in service to the patient as an ally with their own potential for Health. Calling on these skills and resources allows for an interface with the Health of the patient and manifests a treatment that does not simply intercede upon what is myopically perceived from without to be diseased. Rather, "find[ing] Health" allows for the possibility of transformation from within with an enlightened, holistic ease that simply outshines the blunt and forceful nature of "find[ing] disease."

Back to top